Should parents be paid?

by Katy Elphinstone, January 2025

Before considering the question, I’m going to imagine a big blackboard covered in sentences beginning with, "But..."

Sentences like, “But who’s going to pay for it?”, “But why should you get paid for something it’s your choice to do?” and, “But there are so many intrinsic rewards to being a parent!”

And now I'm imagining wiping it all clean with a fluffy duster.

I’ll think about those things later, I promise!

Let’s start, however, at the beginning...

Ten reasons why parenting should perhaps not be unpaid

-

Being a main-carer parent is a lot of work.

A main-carer parent needs food and shelter.

-

They also need to provide food, shelter, clothing, etc. to their children.

Food and shelter (and other bits and bobs), in our society, cost money.

Parenting being unpaid, but yet a great deal of work, is likely to render the main-carer parent a dependent of one kind or another. Being dependent can be quite a powerless, even humiliating, position within society.

-

Main-carer parents, arguably, should neither be powerless nor feel humiliated – as this is likely to be counterproductive to both their wellbeing and performance.

-

Being unpaid leaves main-carer parents open to exploitation and manipulation, due to their dependency upon the goodwill of others or of society as a whole.

-

Main-carer parents are likely to possess the direct knowledge and experience needed to make good judgement calls about the lives and wellbeing of their children. But being relatively powerless and/or penniless renders them less equipped to make those calls, or take meaningful action to improve the lives and wellbeing of their kids.

-

Being a main-carer parent is time-consuming (between care work, emotional support, logistics, domestic tasks, food provision & preparation, getting up at night, and so on, a main-carer parent of young children is usually already working a 100-hour week). This means they lack the time to have a properly paid job, which in turn results in many families living in poverty.

-

If children see their main-carer parent exhausted, depleted, demoralized, poverty-stricken, and worried, they may reasonably believe themselves to be a burden. Guilt, and thinking you must not add to your parent's load e.g. by telling them when you're in trouble, isn't conducive to a carefree and emotionally healthy childhood.

Once, when my kids were small, I spent some time one night looking at job opportunities in a nearby city. Being financially dependent was really getting to me. It only occured to me after a couple of hours... when was I going to do this job? In which hours??

The point really being, here, that so complete is the societal gaslighting around parenting 'not being work' that even those who're doing it, believe this. While having a vague feeling we must be going nuts.

Katy, why are you making it all about money?

You may wonder why I'm talking so openly (in such a vulgar manner!) about money. Aren't other things – besides 'dirty cash' – beautiful, important, and of great value?

Well, money, in our society, is the principal way things (both services and material goods) are obtained. It has so far outstripped any other ways of obtaining things that one could say that, in many situations, it is now the only way.Alongside the exploitation of natural or primary resources, commodification is an important mechanism enabling economic growth. It's a process whereby things – whether materials, services rendered, or use of things such as land, water, and so on – that were previously free, now cost money.

All of this means that a family needs money to get by. There's just no way around it. We can't live in a wood, in a cardboard box, eating mushrooms and acorns. I don't think that's even allowed! (Even if it were possible.)

Finally, I'm not the only one who thinks parenting work (and care and domestic work in general) can be calculated in monetary terms. Believe it or not, it gets calculated into GDP, while, however, skillfully avoiding compensating those who do it. I've described how it's done in this thread.

Work & pay – a beautiful example of circular logic

As a society, we currently think that anything that isn’t paid isn’t work. So if you’re not paid, you’re not working.1Puzzling as this might be to those getting up at dawn to clean, tidy, prepare kids’ lunches, hang laundry, and so on. Apparently those hours before leaving for work and school… uh… don’t exist. Neither do your aching muscles or shaking legs, come 10pm when the dinner things are finally cleared away. Sorry about this, but they’re just a figment of your imagination.

Dependency vs independence

Being a dependent, of any sort, in our society, is (contrary to myth) actually not a very pleasant experience. I would go so far as to say you’re not ‘lucky’ at all. You get patronized a lot. Not listened to. Not taken very seriously.By many, you’re literally scorned – if, for example, you’re a dependent of the state.

Your views, needs, and preferences are generally considered to be of very low priority. It’s made clear to you, at frequent intervals, that you should a) be in a state of permanent and abject gratitude, and b) never complain. There’s a whole raft of gaslighting techniques that will be used on you, should you dare to speak up about any injustices or illogic.

While for those main-carer parents who opt to, or are forced to, also work for enough money for you and your family to live on – there is physical and mental depletion, exhaustion, and (eventually, if the situation continues on for long enough) burnout... to look forward to.

Back to the ‘buts’

Here’s a list of all the reasons we tend to think parents shouldn’t get paid.

I gathered these simply by asking people, when the opportunity arose, the question, “Why should parents not get paid, in your view?” and they obliged me… but if there are any I didn’t cover, please do shout out to me on Instagram, Bluesky, or Mastodon.

1. Who's going to pay?

I’m afraid I’m not going to answer this question in a linear way. Instead, I’m going to try to demonstrate – briefly – how misguided our current economic system is, and therefore what an odd situation we're in.

We seem to have equated value inextricably with price. Someone might say, what is the value of this painting, this house, this field, this person’s work? And the other might answer, $10,000, $100,000, $30,000, $25 per hour.

I recently played a fun game with my kids. We thought of a whole bunch of occupations, trying to make them as varied as possible in terms of social status and activities undertaken. We had a bus driver, investment banker, doctor, nurse, forest school teacher (my kids did Forest School at the time), Greenpeace dinghy driver, musician, arms trader, mother (my suggestion, I confess), rubbish collector, photographer, and so on.

The occupations – about twenty of them – went into the first column of a large table.

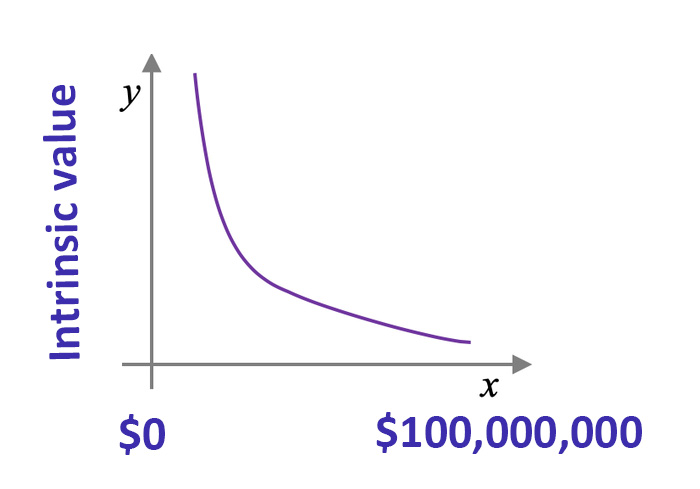

The next five columns were all headed ‘value…’, and (below that) separated into categories, as follows; ‘to yourself, to your family, to your community, to your society, to the planet.’ We decided to overlook the monetary value of any of the professions (for example, a banker’s family might benefit from them bringing in a good salary) and focus solely on the intrinsic value of the occupations. We filled the columns using values from 0-10, based on what value we together agreed we thought the work had within each of the five spheres (I’d so urge you to do your own – it was fun, and I’d love to add more data to our little study, if you’d let me know your results).

In the last column, using my phone to search things up (we were in a café at the time), we filled in (more or less) the average salary for each of the occupations. And, finally, we drew a lovely graph in felt tip pens.

Salary on the x-axis; our adjudicated value (totalled from the five columns) on the y-axis. And… da-da!... it made a beautiful inversely proportional sweep. So. To extrapolate. It seems – at least from our ‘back-of-an-envelope’ experiment here – that the more you earn, the… uh… less intrinsic value your work actually has.

Huh? So, what were we just saying about value and price??

I recently saw a quote, reportedly from a billionaire (though I think it may have been a joke). It went something like, “What about when 3-4 people in the world are trillionaires, and the rest are just freeloading?”

There have been various economists who’ve been brave enough, and had large enough audiences, to point this calamitous error of logic out to the public with any degree of success. Three names that jump to mind are Varoufakis, Mazzucato, and Marx.

Respect.

So (sorry for wandering) – who’s going to pay?

Uh. Hmm. Could the arms traders maybe pay, or the hedge fund investors? Or, better still, the billionaires (soon to be trillionaries, I hear)? I know. Silly joke. Apologies. I suppose my point is, instead of asking, “Who's going to pay parents?” we should perhaps first be asking, “Where are all the money, power, and resources in the world heading off to so fast? And why? And with what effects?” More on this later.

2. Children are a drain. They cost money and don’t generate any

That’s true – but only temporarily. The same children who currently cost us money to raise will be holding up our social and economic system once they’re adults – and we’re old. They’re our future taxpayers, producers, care workers, and consumers.

In fact, ensuring that people pay privately for the raising of those children, but that the money they later generate goes into the economic system (as their tax pays for pensions, services… and they make investments, are the workforce, and buy consumer goods, etc.) is quite a savvy – if not entirely logical – move, now I think about it.

I've done a little thread about this, on Mastodon.

3. “You brought it upon yourself”

Hm – only, there are quite a few occupations that people brought upon themselves, or created from scratch, which can be very lucrative, and yet I don’t see us having much trouble with it.

A few examples could be draining marshlands, exploring continents, appropriating land, constructing buildings. I think the problem here is that we’re equating two things that are actually unconnected – the ‘making something from scratch’ or ‘bringing something upon oneself,’ with the belief that the activity should be financially unrecompensed.

4. Environmental reasons

If you have children, there are humans who wouldn’t have existed but for you, who’ll now use resources and reap their share of destruction upon this planet.

This, to me, represents a very good argument against humans having children! There’s a statistical problem, however, when we apply it to the question of whether parents should get paid. People don’t have fewer children when they’re poorer and have lower social status. They have more.2As for fears about overpopulation, I can’t possibly explain the situation better than Dr. Alice Hughes has done in her interview Dispelling the Myth of Overpopulation, where she addresses ecological issues as well as societal ones.

Finally, I can think of some activities that are, arguably, more environmentally destructive than having children... such as fracking, logging, or open cast mining. And yet we don’t argue that those activities should logically not get paid.

5. If parents get paid, won’t people have children just for the money?

I’ll start with a bit of background, but I promise I won’t take long to get to the point.

There are now many places in the world where birth rates are falling. In fact, so much it’s a threat to the economic and demographic wellbeing of those countries affected. The countries with falling and aging populations tend to be the better-off ones – and, incidentally, those where women have more rights (and therefore choices).

Let's look at this objectively. Would you voluntarily choose a tough and demanding job with no holidays, no salary, long hours (including night shifts), and no sick leave? Doing work that isn’t considered work at all, and which renders you a dependent, throwing you irreversibly onto the charity of people with a bit more power than you?

If the answer is, “Er… no!” let’s move onto looking at the history of this.

For many years, after (in most countries) women’s rights became a thing and our bodies and labor were no longer legally owned by our husbands and fathers, society used our youth and ignorance, and heavy social pressure, to get around this problem. Girls were simply expected to get married and have children, while being told next to nothing about what that would actually entail.

I recall reading an article by a woman who said that when she told people she didn’t want to have children, they "acted as though I’d just said I enjoy killing kittens for fun."

Parents, education, your community, and media all conspired to make you believe you weren’t complete without children, and that’s all a good woman wants, besides perhaps a washing machine. Simultaneously, women experienced many obstacles in the workplace and were paid low wages. Maybe this made housework, childcare, and the fairytale-sounding ‘being provided for’ seem relatively attractive.

The workplace has gradually become more accessible for women, in richer countries at least, and people are now older when they have kids. There's more information and personal choice involved. So those incentives – or rather, disincentives – are losing traction.

And birthrates are falling. People are choosing not to have children. Even when they're paid to do so.3 It’s a problem the extent of which we have yet to discover.

I’d be interested to see how giving parenthood a secure foundation of social status and financial support would impact people’s childbearing habits. After all, we’ve already discovered how to make birthrates fall – through improving conditions for women.

I’m sure all of us in countries where there’s some form of child support have heard people say, about one mother or another, “Oh, she’s just having children so she can get benefits and not work.” I tend to react to this by cracking up laughing.

Not work? Oh my. Ouch. But it isn’t very funny, not really... I suppose they don’t notice when that same mother is seen grey-faced at the supermarket, her arms popping out of their sockets, lugging bags, infants, and shopping. Unless her baby cries, or she fails to smile and talk sweetly, in which case we might say (or just think, if we’re reasonable people), "Can’t she do any better than that?"

6. Parents aren't formally qualified...

... and why pay someone to do something they require no qualifications or training for?

It took me a minute to get my head around this one. To get my breath back, really.

In our society, I don't think qualifications only serve the purpose of causing someone to do a job well (although, of course, in many cases they contribute to it – you can't very well be a surgeon without knowing a lot about human anatomy).

The knowledge required to do a job well can be got from many sources. A surgeon could have learned everything they know by, for example, being an apprentice and having open access to all the study material they needed, without ever setting foot in a university nor sitting an exam.

Qualifications are supposed to be simply about demonstrably measuring our expertise on a topic. But, in reality, this is not their only purpose.

They are also designed to exclude a large number of people from doing things – specifically, high-status and well-paid things. After all, you need to already be quite privileged to go to a university.

So, qualifications have a whole other purpose besides the noble one of making sure people will do their jobs well. To maintain the power structure and keep people in their places.

Frankly, I get goosebumps at the idea of these principles being applied to parenting, too.

But let's stay on-topic. Main-carer parents have a natural bond of love with their children (even if sometimes this has been tampered with by their past traumas). This, I would argue, is qualification numero uno.

As I wrote in my book, How to Raise Happy Neurofabulous Children, "The first and greatest resource of a parent is a deeply loving heart. And the second one is a vastly open mind."

I adhere to that. And I don't think you need formal qualifications to possess them. I think you need healing... and, ideally, some proper support from your community and society.

7. Who would parents report to, if they were paid?

Yes, who would be their ‘line managers’?

Well, this question first assumes that parents are currently their own managers or else managed by someone competent and qualified. Neither of these things are the case.

At the moment, if you’re lucky, money for your housing, food, and other day-to-day things gets provided by a partner, your parents, or – in some countries – a basic amount may come from the state.

I’m just having a smile to myself as I remember my partner asking me questions about my day’s achievements in my then role as homemaker and mother. I said to him, rather crossly I confess, “You’re not my manager and I’m not your employee, and this isn’t a performance appraisal.” Hm. I think, without realizing it, I’d rather hit the nail on the head.

Musing: I wonder if there is any more vulnerable position? Relying for your subsistence on arbitrary support over which you have almost no control, with little ones in tow who rely on you for everything and can’t be brought along to any formal job (even if you had the hands available to do said job). Spending all your time and energy on work that ‘isn’t even a job’ – but one where you doing it properly will mean the difference between your child suffering and them being okay. Oof. Even though my partner was well-intentioned, no wonder I was looking at job adverts!

8. Why pay for something that’s intrinsically rewarding?

Woah. This one does not say very much for human nature, nor what human life on Earth consists of. So, let me get this straight. Are we saying here that our worthwhile, um… paid… jobs, should be things that we humans find fundamentally pointless and must be cajoled and bribed into, and then hate doing all day long?

Am I the only one who throws up my hands at this and cries, “Why are we here, then? Why was I even born?”

Plus, I can think of a few professions whose protagonists may reasonably find quite intrinsically rewarding that do get paid… and yet society doesn’t protest too much about it. Football player, nurse, teacher, architect – I could think of more.

9. Wouldn’t paying parents just be another form of commodification?

Commodification came about through people's desire to make profits. This is why it invariably involves exploitation in some form, and a power differential favouring the person who's doing it.4

Slavery is an extreme form of commodification, where human beings are assigned an economic value and traded.5

This begs the question, “Who makes the profits? Who benefits?”

In the case of parenting, the beneficiaries would be children and their main-carer parents. Who currently have little power or voice within society. I don’t think it would be too far-fetched to theorize this might be the sole reason why it hasn’t been commodified yet.

An exploitative structure – one we’ve all got used to

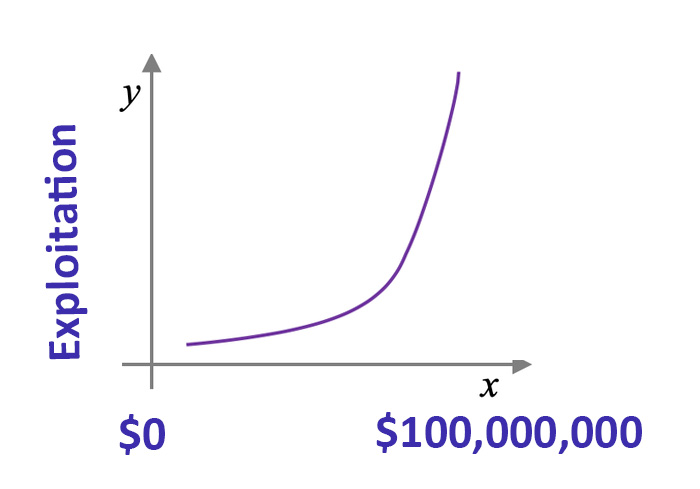

I think what we’re really looking at is a different kind of logic altogether. One that we can’t admit to ourselves even societally (i.e. on a collective level), let alone individually. The real truth is, we’ve all become very used to the concept that the only truly logical way to make money – to reap benefits, to live comfortably, and so on – is to exploit.

Exploit markets, desires, raw materials, labor. Anything, really.

When we exploit things, money comes out of it. That’s how things work. It feels nice – a relief – to be able to openly express that, after the previous section’s wandering reasoning.

The exploiters can then use their money to pay others to provide them, for a fee, with whatever services they require.

But we’re all in a kind of fog around this concept of exploitation (I suppose it does not make us – humanity – look very good). If asked, “Why do we work?” we answer, “Because it's useful,” “Because it helps,” “Because we’re being productive.”

Only… what is it helping, and whom? What does it produce? And what are its outcomes?

Perhaps a more honest way of responding to the question, “Should people get paid for parenting?” would be, “No. Logically. Because it neither exploits anything nor directly serves the exploiters – those (logically) with the money. Plus, why pay for something you can quite easily get someone to do for free?”

True. Main-carer parents cannot stop working. The people they love most in the world – their children – would directly suffer. It’s a hostage situation. Yes… they will do it for free, or for very little. And if we can gaslight them – and ourselves – into thinking that they aren’t working at all, well, so much the better!

This little blind spot in our collective consciousness would also account for the pattern my kids and I discovered, as to how much money the various occupations get paid.

If pay isn’t particularly connected to whether things have any real, intrinsic, value (as our ‘elephant in the brain’ would inform us), but rather whether – and to what extent – they either exploit things or provide those who exploit things with services they’re willing to pay for. And whether we possess the traction or 'power to punish' (e.g. by direct repercussions to those they love most) to make large groups of people do certain jobs for free. Well, in that case, our graph would make perfect sense.

Now I’m curious. Let’s re-do our graph.

And there, I think, we pretty much have it.

The cute myth that you get wealthy by working hard… well, it’s a myth. One that beautifully serves those in a position to sit back and watch their wealth growing larger, without any requirement to do anything. In my article on morals and inertia I've explored this phenomenon in more detail.

The flow of resources

The main stakeholders in this situation, however, are not the parents... but the children.

Children are a highly vulnerable population, possessing no real say in things, no vote, and no resources of their own.

Under our current system; resources, money, power, and status all flow to where there’s already an accumulation of those things. Away from where there’s a deficit of them – a lack, or a need. See my article on the dynamics of blame for more on this.

Imagine it like a mountain range. With more and more matter being added to the mountain tops as it’s excavated out of the deep, ever-deeper valleys.

To my autistic brain, this is absurdly illogical! Surely things should flow towards where there is most need of them? And away from where there is already a surplus?

This isn't about the deckchairs

Words like ‘capitalism,’ ‘liberalism,’ ‘feudalism', ‘socialism,’ ‘communism’. These all seem, when put into practice… hm… rather like the types of furnishings on the cruise ship. When the ship itself is sinking.

As Audre Lorde so aptly put it, “The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house.”

The belief systems of some indigenous cultures look a bit different from those of mainstream global society. And, in certain tribes, people are rather less competitive and individualistic.

There are stories about this. I remember hearing about the children of a certain tribe being put into a large circle, and told that whoever got to the pile of goodies first (the ‘winner’) could have them all. The children, puzzled, looked around at one another… but then they linked hands and ran together to the pile, where they sat down and happily shared the fruit.

I’ve experienced this attitude myself among the San people – commonly known as the Bushmen – in the Kalahari Desert in Southern Africa.

After our visit, my son (then six years old, and deeply interested in logic and fairness, as so many autistics are), asked me often, “What would the Bushmen do…” His questions were things like, “What would the Bushmen do if someone among them was a bully and wanted everything for themselves?”, “What would the Bushmen do if there was a family who didn’t have a home?”

Partnership vs domination; trust vs distrust

We’re currently living pretty thoroughly in the paradigm of the ‘dominator model’ of society, and indeed reality.6

The principles of this model are:

- • Universe won’t provide

- • Each of us is isolated, an 'individual'

- • It’s a dog-eat-dog world out there

- • If you don’t compete and fight, and win, you’ll be eaten

- • Humans are lazy, good-for-nothing creatures, who need to be punished or cajoled into action

Let us imagine, instead, a less violent world – one based on partnership rather than domination (what we observe in certain indigenous cultures fits more into this paradigm of a ‘partnership model’). The tenets of this are:

- • Universe will provide – trust

- • What one of us has, we all have

- • Kindness and action feel good, and humans do these things naturally

- • We’re connected with each other

- • Everything is connected

Two words that sum up the two systems, respectively, are: ‘trust’ and ‘distrust’.

In one model, you can relax. Others, and the universe, have your back (whatever unexpected forms that might take). In the other, no one has your back. You can trust nobody, and nothing. It’s a cruel world that’ll hurt you given half a chance.

I probably don’t need to say this, but it’s a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The world genuinely isn’t safe…. because no one trusts each other. Therefore, everyone is profoundly untrustworthy (especially if their fear is triggered, which is, for most of us, all too often), and prone to dehumanizing and exploiting others at the drop of a hat.

Spheres like parenting, education, employment, the economy. Everywhere we look, we can see those tenets of distrust and unease – fear – at work.

Is there any chance we can revert this?

Resources – whether money, time, energy, focus – should, I believe, flow to where there is most need. Not to wherever there's the most exploitation going on.

So what would the Bushmen do if there was a bully (a defended, distrustful, competitive person) in their midst? What would they do if a family had no home, or nothing to eat?7

I imagine, being still much closer to a 'partnership' belief system than we are, they might find it within themselves to trust... and heal... and share.

The question is, can we?

My dream is that we may manage to build a new ship, together.

One where the labor of looking after our young is seen, respected, and has a secure foundation of practical and financial support.

❤️

Footnotes

-

It’s estimated that if women around the world received minimum wage for every hour of their unpaid labor, they would have contributed about $10.9 trillion to the global economy in 2020. This is more than twice the size of the global tech industry that same year ($5.2 trillion).

Reference: Epker, E. (2023). Women Handle 75%+ Of All Unpaid labor. Their Health Pays The Price. Forbes. - The main reasons for poorer people having more children are; a) higher infant and child mortality rates, b) more hands to carry a heavy labor burden, and c) security for the future, i.e., there will be someone to look after you in your old age. This study details the trend demographically & statistically: Skirbekk, V. (2008). Fertility trends by social status.

- "The drop [in populations in many countries] has frightened lawmakers and commentators alike, with headlines warning of a coming 'demographic crisis' or 'great people shortage' as economies find themselves without enough young workers to fill jobs and pay taxes. To stem the tide, the world’s leaders have tried everything [...] to five-figure checks to veiled threats, all to relatively little avail." From the article, You Can’t Even Pay People to Have More Kids. Population Connection. (n.d.).

- I see it a bit like good cholesterol and bad cholesterol. We say we have 'high cholesterol' when we actually mean just the bad stuff. The definition of 'commodification' is that things that previously didn't have a monetary cost, now do. But in common usage, and (I believe) the reason we have such a niggle around things being 'commodified', is because (just like with cholesterol) when we use it in day-to-day speech, it's only the unhealthy kind we mean. The kind that generates profit and benefits only the wealthy, and does not in any way help the vulnerable or reddress power imbalances.

- Zeuske, M. (2023). Migration, Slavery, and Commodification. Oxford University Press eBooks, [online] pp.311–334.

- The theory of the 'dominator model' vs the 'partnership model' is known as Cultural Transformation Theory, and was first proposed by Riane Eisler, a cultural scholar, in her book The Chalice and the Blade. Thank you to Jeff for introducing me to Eisler's work through his own writings on The Autistic and the Blade.

- The autonomy and rights of the women of the San people has reduced drastically in relatively recent history, along with the tribe being forced to settle and assimilate into modern society.

Images reprinted in this article with permission from the photographers as follows:

1. A young mother holding her baby, by Youngoldman.

2. Doing housework, by Marie Hoosier.

3. Household chores, by Anandamoy Chatterji.

4. Woman with children in India, by Salvador-Aznar.

5. Money, by David Kivlin.

6. Private Jets Parked Side by Side at the Airport, by Andrew Warren Gould.

7. Spoil Alert, by Dave Hill.

8. Distraught toddler carried by mother, by Vanilnilnilla.

9. Picture of How to Raise Happy Neurofabulous Children, by Katy Elphinstone.

10. Father and Daughter wall mural, by Diane Wildowsky, and more about the artist of the mural here.

11. Bella and Joshua , by Kevin Whitlock.

12. Near the top, by Jeffrey Danneels.

13. Bushmen, by Catherina Unger.

14. Don Khon, by Mauro 'Alexander 3rd of Macedon'.